|

Hunters can compensate for losses to hemorrhagic diseases.

JEFFERSON CITY– Conservation officials say they don’t plan immediate measures to compensate for deer losses to hemorrhagic diseases, but they will look carefully at harvest information, reports of sick deer and hunter surveys when considering future hunting regulations. They note hunters’ key role managing deer numbers and suggest shooting fewer does if hunters notice declining deer numbers.

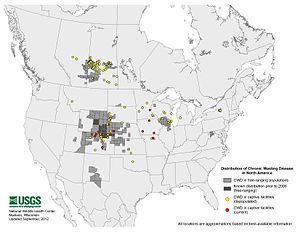

Two hemorrhagic diseases – blue tongue and epizootic hemorrhagic disease – occur naturally in Missouri’s deer herd every year. They are unrelated to chronic wasting disease (CWD), which currently is found only in Macon and Linn counties.

Both varieties of hemorrhagic disease are spread by midges, biting flies that breed near water. Outbreaks are worse in drought years, because midges have a better chance of transmitting the disease among deer concentrated around water holes.

“This year’s drought was one of the worst on record,” says Resource Scientist Emily Flinn. “Missouri had significant hemorrhagic disease outbreaks in 1980, 1988, 1998 and 2007, but this year’s outbreak was more widespread and severe than any previously documented hemorrhagic outbreak in Missouri.”

According to Flinn, some counties may have lost 15 to 20 percent of the deer population to hemorrhagic disease countywide, with localized areas within counties having upwards of 50-percent mortality. However, county-wide assessments can be misleading as EHD may impact one part of a county and have little impact elsewhere in the county.

Flinn says depending on the situation, regulations changes might need to be considered. Regulations were changed following the 1988 hemorrhagic outbreak, but not in response to the 1998 outbreak.

“Reported hemorrhagic disease cases, harvest totals, hunter surveys, herd size, and other factors will assist us in determining whether regulation changes should be considered,” she says. “Hemorrhagic disease losses could be reflected in some county harvest totals this year, but those totals will likely not tell the whole story. Typically, harvest stays up for a year or so after an outbreak and then declines. This is because hunters typically still see enough deer to shoot approximately the same number as before, delaying the harvest decline, but causing a larger decrease a couple years down the road.”

Flinn adds, “There is the possibility that decreases in deer populations due to hemorrhagic disease might not be as apparent to hunters because this year’s low acorn production will make deer more susceptible to harvest, especially in the southern Missouri.” Most hunters don’t use all their antlerless permits and can cut back doe harvest if deer populations appear low in their hunting area.

In some areas, deer populations will recover in a few years because of low doe harvest. However, some areas are less likely to rebound quickly due to high doe harvest, potentially leading to poor hunting conditions in the coming years. Therefore, if hunters do notice a significant decrease in deer sightings or found numerous dead deer typical of hemorrhagic disease this year, then they should consider harvesting fewer does. Flinn says overall Missouri has a strong, healthy deer herd.

Citizen reports of sick and dead deer received this year are a key source of information for determining which areas are hardest hit by hemorrhagic diseases. Counties with the most reports this year included Chariton, with 317 reported deer deaths as of Nov. 26, Osage with 313, Benton with 239, Boone with 178, Monroe with 177, Daviess with 176, Shelby with 169, and Randolph with 158. However, the highly localized nature of hemorrhagic disease can be seen even in counties like Benton and Osage, where some areas reported no hemorrhagic disease cases, while other areas had significant deer mortality.

Further information about hemorrhagic disease and a map showing where in Missouri the 6,100-plus reported cases occurred are available at mdc.mo.gov/node/16479.

-Jim Low-

No comments:

Post a Comment